Writer, former publisher, teacher of writing and co-host of the Book Club, Stephanie Dowrick, makes a plea that we would all invest more in writing, in living writers - and in our own personal and collective intellectual and even spiritual development. Buy more books. Read more widely, she argues. Support bookstores... support libraries... contribute to the world of ideas and ideals through your own constant and committed reader activism.

I've been involved in publishing, editing, teaching writing and writing for many years. I landed my first, exhilarating publishing job in 1972 (at George Harraps in London). And that's quite some time ago. There are many current mature, prize-winning writers who were not even born then! So I think I am fairly entitled to claim that there has never been a more difficult time for professional writers to make even the smallest living from their writing. Yes, I know some prominent writers are earning mega-bucks (tho' in reality it's very few), and - more positively - writers are using new media in all kinds of creative ways to reach readers. But many of those "creative ways" return few if any dollars and cents. And while it can be exhilarating to reach new readers and interact with them, most writers still have to pay their way.

Don’t assume that just because your favourite authors “love” writing, they can survive on inspiration and affection alone. They need your support.

When I mention to readers and newer writers that things are increasingly tough at least in the English-language writing world, they often assume it's because more and more readers are buying their books on-line. On-line sales do, though, return at least some royalty to writers (though often smaller in real terms), so that's not the entire answer. At least two other reasons stand out.

The first is that many real-time bookstores have closed, including significant chains in both the USA and Australia. This is where the losses from on-line buying really show up, and the knock-on effect for writers is brutal. Real-time bookstores allow for and facilitate a depth of browsing that on-line buying cannot. Holding a book in your hand, you may be far more likely to take a punt on it (and on the writer who created it) than when you see an unfamiliar postage stamp-sized image on the screen in front of you.

Book-buying is, for many of us, instinctive. That lovely sensual adventure of casual bookstore browsing and pouncing will be lost unless we actively and emphatically support the real-time bookstores that remain to us. Even now, many bookstores buy their stock increasingly conservatively (the same books everywhere...). We need to make it worth their while to stock books that are not entirely predictable. We also want to show them - through our buying and our conversations with them - how keen we are to discover and read writers whose work matters.

One more reason, and this time it's more hunch than reason, but it seems to me that increasingly people are finding reasons not to read books and instead to interact with social media, to pick up an article or two on line, or to seek out an encapsulated version of whatever it is that interests them. Time is the big cry here. Yet we continue to have the same 24 hours in every day that we've always had, so I suspect it's more a question of attitude than time itself. It's also a matter of what people explicitly value. As long as people tell themselves they haven't time to read, they will turn on their tv or computers instead. And the losses are very real.

|

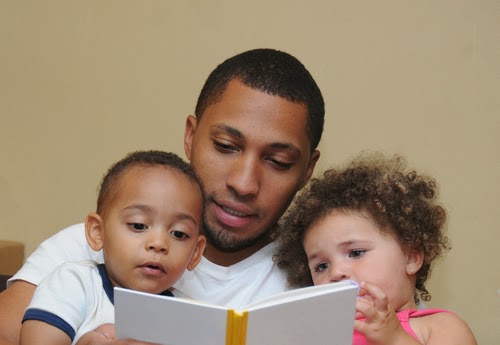

| The greatest gift we can give children is to show them how much we value books - by reading to them and especially through the time we give to our own reading. |

The losses are real in our individual intellectual and spiritual development. And in our collective development. Good books feed and stimulate the mind as no other media can. A well-written magazine, newspaper or on-line article may be fascinating. It may even be mind-changing. But a good book - a book that's saying something of real value - will always offer a far greater depth of thought, reflection and risk than a short article or a Facebook post (or a tweet) ever can. And I strongly believe our hungry minds need that depth. If our lives are to be half-way satisfying and meaningful, we need to grow in intellectual agility as well as in experience and wisdom. We need to be challenged, jolted and sometimes soothed. We also need entertainment, perhaps even distraction; fine writing also gives that. To be "lost in a book" is, for many of us, an experience close to bliss. So we all need to be made newly aware, I believe, that real books, the books in which we can lose and re-find ourselves, are crafted over years, take time, take massive commitment, take obsessive amounts of re-writing...in order to give what readers seek. They don't happen by chance. And they cannot happen at all if there are insufficient readers willing to buy, read and support them.

What can you do? Lots, I would suggest. Here are some initial ideas. I'd love you to add more in the comments boxes below. Or add them on my Facebook page. Can we save good writing and good writers? I believe we can - and must.

1. Identify the writers you care most about. Know who's writing the books that actually enhance your thinking and your life. Buy their books. Give their books to others. Write positive, encouraging on-line reviews about them. Talk about them. Make sure your enthusiasm is contagious and active.

2. Read adventurously. (No need to see if a book is in the top 10 before it impresses you. Many brilliant, tender, insightful, wonderful books never will be.)

3. Value books and the time you give to reading. We encourage this in children then often find reasons why our own reading is left to the tail-end of the day. Yet what other small investment of money and time can enrich our lives so magnificently?

4. Use public websites - including on-line bookstores - to write brief, positive reviews of books that matter most to you. Share details with others of websites where readers' reviews are being written and enjoyed. Contribute to them. Enjoy your new role as Writers' Advocate.

5. Use social media (FB, blogs, Twitter) to stay in touch with writers. Actively “like”, “share” and spread the word about their work. Let others know what it means to you. Post reviews and discussions on your own social media. Develop and value your "reader's voice".

6. Join or start reading groups: the social benefits are terrific and you will certainly broaden your mind as well as your reading.

7. If you have local booksellers, support them. Tell them about the books that have moved or impressed you.If you are buying on-line from Australia or NZ, please please avoid buying US editions of local writers. The "cheap" editions return virtually nothing at all to the writer. And further weaken local booksellers and publishers as well as the writer.

8. Join your local public library - but also take the time to request copies of every book you wish other people would read. You will benefit many readers - and writers.

9. Many books are now available also in audio editions. This can give you a fresh perspective on favourites; it's also a way of introducing worthwhile books to people who may claim to have no time to read but have to drive a car to work, or would listen to audio while doing household tasks.

10. Give books for all and every occasion. And when there is no "occasion", give books anyway!

Stephanie Dowrick's most recent book for children is The Moon Shines Out of the Dark

Her most recent book for adults is Heaven on Earth - Gold Medal Winner in this year's Nautilus Awards: Books for a Better World. (All her books are available postage free within Australia.)

Stephanie has a public Facebook page where you can read daily inspirations - but we hope you will also want to read and respond to her books!

Feel free to comment in the comments box below. We love to hear from you.

We also have bookstore links above right - both local to Australia (for local books PLEASE), and for our readers in the Northern Hemisphere, we have links for you also.