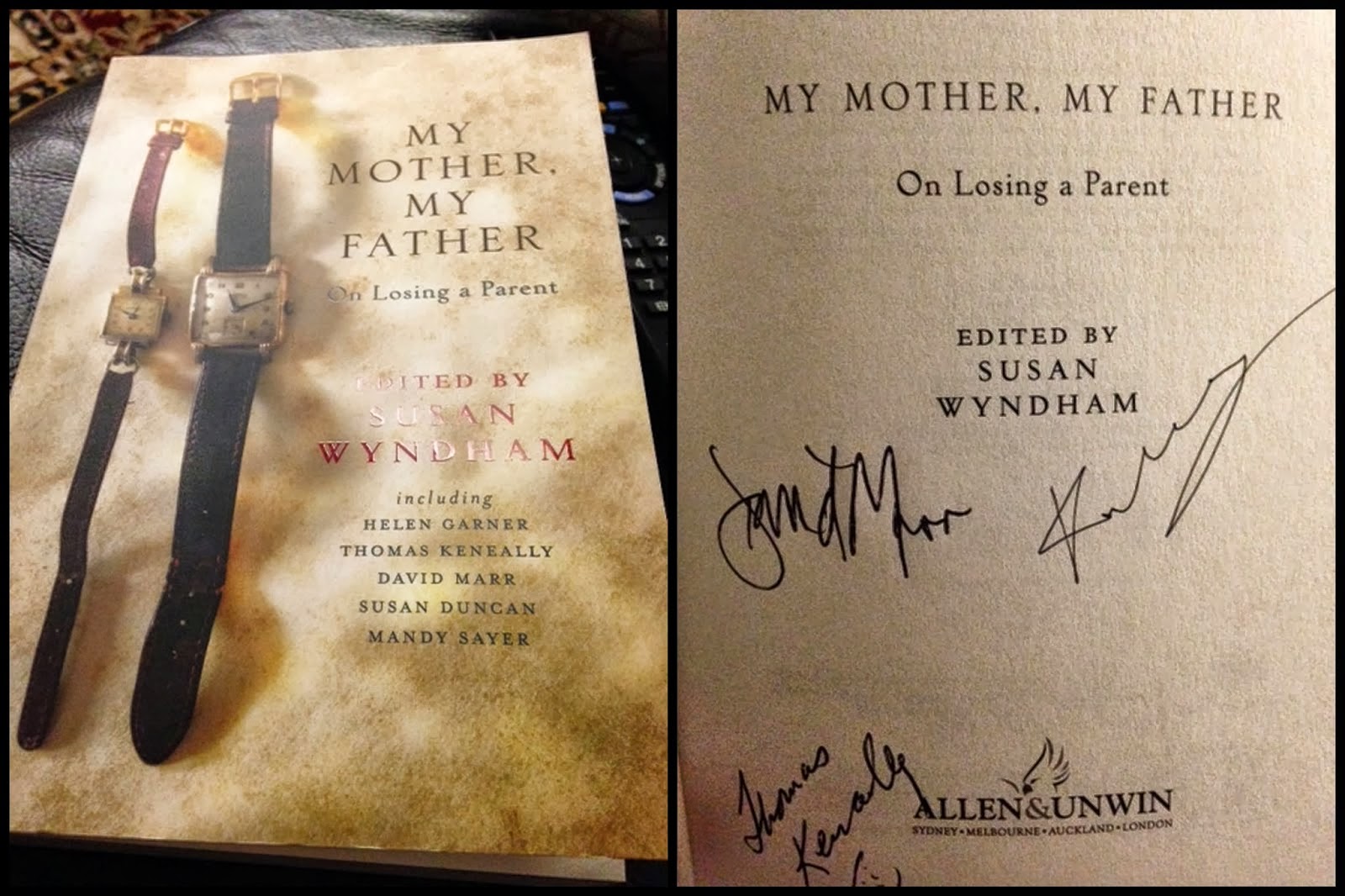

Stephanie Dowrick - co-host of this Book Club - reviews and greatly admires My Mother, My Father, literary editor and commentator Susan Wyndham's fine book on "Losing a Parent".

Editor Susan Wyndham chose her contributors wisely. Each allows us through a distinctive voice to discover more of what it may mean to survive, to re-make oneself as an adult orphan, and to remember.

Mourning a beloved person makes us all vulnerable, but this can be dramatically intensified when it is the once-powerful parent who is laid low, ill and dying and when the parent/child relationship is – often after many years - abruptly centre stage. Kind Tom Keneally, for example (surely one of Australia's genuinely 'great' writers), remembers his asthmatic childhood and the mother “who never lost her faith in me”. Yet that same mother (who at 94 was still ringing him to check “the latest shift in asylum-seeker policy in that morning’s Herald)” could say things to this formidably accomplished writer that would “transform me, in my sixties, into a sullen fourteen-year-old.”

The pictures of family life that emerge are credibly unpredictable and so are the deaths and their continuing reverberations. Neither the happy nor the unhappy families are alike in this book. And while dying is the pivotal drama of the contributions, it occupies and preoccupies the writers differently. When Mandy Sayer misses her mother she likes “to wear her clothes – or, more precisely, her knee-length pink nighties.” Linda Neil quotes a nurse at the hospice where her mother died a slow death from Parkinson’s disease saying of death, “It’s a strange and precious process that you are lucky to witness.” David Marr opens his chapter baldly: “Their deaths were awful.” His parents’ lives though, as he shows, were not awful; far from it.

Jaya Savige reveals two losses: the mother who died too early; the biological father who had disappeared: “He will never know how she filled her children with awe one day by paddling to the mainland and back on a surf ski…setting out from a small patch of sand to which I would also later return…” Kathryn Heyman also writes eloquently of two devastating losses: the father who “has never been good at talking. Or embracing. Or making eye contact”, and her warm, adored and adoring father-in-law unwittingly making her connection with her own father more, not less unsettling.

In most of these contributions both life and death are secular events. There’s truth for the writers in that. Nonetheless, the standout contributions for me – among these riches – are journalist Nikki Barrowclough’s unforgettable chapter and editor Susan Wyndham’s own exquisite account of her intimate relationship with her mother (“My life without her was unimaginable…”) and her mother’s faith not in Christian Science only but that death would take her to “another stage of experience”.

There are several deaths in Barrowclough’s chapter: the painfully anticipated death of her mother is just the first. That she is able to share this series of experiences with us, and with such grace, is extraordinary. So is her quietly growing awareness that anything we can know about death - and much that we can know about life - is only the beginning of more knowing. What is death? What is the meaning of a particular death in the lives of the people who are “left behind”? Helen Garner writes yearningly of unfinished business (”I never sat my mother down and pressed her about the past…”). David Marr – in this his father’s son – writes of “facing facts”. We can be grateful to all these generous writers for the life that’s in their pages. We can also thank them for a needed, deepening witnessing of death.

Stephanie Dowrick’s most recent book is Heaven on Earth. An earlier version of this review appeared in the Age and in the Sydney Morning Herald. We would welcome your comments on this or any other book that we are so pleased to recommend; the comments box is immediately below. Also, we do offer book buying opportunities through the links on the upper right of this page and please do use this direct prompt sales link to My Mother, My Father (postage free in Australia).