I don't want to know where You are;

speak to me from every place.

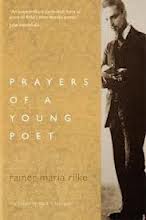

Rainer Maria Rilke is one of the leading poets of the 20th-century, and one of the great visionary poets of any age. This landmark publication of Rainer Maria Rilke, Prayers of a Young Poet, offers Rilke's complete prayer-poems - written in the persona of an icon-painting monk - "as he intended them". The translator is Mark S. Burrows, who also shares his profound, empathic and highly poetic response to Rilke's work in a substantial introduction.

speak to me from every place.

Rainer Maria Rilke is one of the leading poets of the 20th-century, and one of the great visionary poets of any age. This landmark publication of Rainer Maria Rilke, Prayers of a Young Poet, offers Rilke's complete prayer-poems - written in the persona of an icon-painting monk - "as he intended them". The translator is Mark S. Burrows, who also shares his profound, empathic and highly poetic response to Rilke's work in a substantial introduction.

Prayers of a Young Poet is reviewed here, as a letter to Mark Burrows, by Doug Purnell, a writer, former academic and Uniting Church minister and now full-time visual artist.

I'm living just as the century departs.

One feels the wind from a large leaf

that God and you and I had written on,

which turns above by hands no one knows.

One feels the radiance of a new page

on which everything could still come to be.

One feels the wind from a large leaf

that God and you and I had written on,

which turns above by hands no one knows.

One feels the radiance of a new page

on which everything could still come to be.

Mark,

The book came....beautiful and profound...lovely to hold and touch. Then I read your intro and you touch something profound about what it is to be human. You value, through Rilke’s work, the ambiguities, the uncertainties, the "not-knowingness" that Rilke’s poetry values, names, holds up and uses to open the divine. Your introductory essay I read and then have kept returning to. You use your knowledge of Rilke to encourage a journey into the deep, into uncertainty and the ambiguity of life. You invite us into and to live, "the open". You give me a sense of God who is both vast and always becoming and can never be dogmatically known.

You are a gifted poet and your translation of Rilke sings his song in ways most accessible and engaging for me: no mean feat.

And now, I am sitting by a small stream, Tumbarumba Creek, in the high country of New South Wales, a place once known for its timber mills. I went to bed with the sun and woke a while after the sun had risen. I fried some bacon, tomato and an egg for breakfast. Drank coffee while eating home-made marmalade on toast. Then I have sat quietly by the stream reading your book.

I studied poetry for three years at university. In those days (though I didn’t know it then) it was the closest the university had to offering an opportunity to reflect on the arts, on the creative process. Certainly there were no courses in the fine arts. I am sure that studying poetry helped me in ministry and I preached often, and more often as the years went by, on or from the Psalms. It was the poetry, the imagery, the metaphor, the ambiguity, the possibility. Ideas about life and God were not tied down. I haven’t read much poetry other than that since my university days.

|

| Beautiful and profound...lovely to hold and touch. |

Rilke speaks to God as a lover would. Rilke tells God how much he loves. Rilke describes the character of God: not out there, not sculpted in rock, not idealised; rather like a lover might describe his beloved with enchantment and possibility and openness. It might sound absurd: I have been taught over and over to say, “God loves me”. It is much more difficult for me to say, “I love God”, or to say that slowly and thoughtfully, as a lover might.

Rilke speaks to God as a lover, and always with a personal address: "You".

In each poem I find lines that I underline, emphasize, write notes around. This made possible because of the Rilke’s thought and because of your poetic voice. You have taken ideas in one language and translated them to another in such ways that they sing, that the song comes alive. I am savouring words, words sung to life, and ideas.

There I’d have dared to squander You,

You, unbounded present!

An interesting thought: are we willing to squander God? Then later, an intriguing line:

“…don’t squander your blood in blind passion!” I wonder how this line, this idea relates to the crucifixion story. How is it different for God to squander God’s blood and for me so small before the vastness of God to squander God?

(Somewhere in my reflection, I think of my children. When I nurtured them in life I wanted to share with them Christian community and the profound truths that come within the Christian narrative. I wanted to share with them what it is when I read this poetry. I struggle to find words for the next bit. I know that they respect that I find something important in both - the community, and its narrative - I am not sure that they could name what it is. I think at the same time they have decided, not that they don’t want it, rather that they don’t need it. Rilke is not lamenting the attitude of others, nor is he lamenting the action of God. He is speaking from his solitude, from the depths that he has entered and with the openness of one who is present in the midst of life.)

“You aren’t after enjoyment but rather joy.” I’d never consciously thought they could be different, and the way they are written here, they are.

Mark, I sit here beside the stream. The gentlest of breezes sways the long fronds on the willow tree. The birds sing their song. No soloists, somehow an orchestra. A duck dives in the stream. Earlier she had come down in midstream on the current, then stopped, turned to face upstream and paddled sideways out of the flow. I can imagine you enjoying the quiet of this place and this moment as I do.

I am heading down into Victoria to spend some days camping with friends and to help another friend celebrate being seventy. My neck was restored to life after four or five sessions with the physio, and I took off early so that I could have a couple of nights along the way camping on my own. Enjoying the solitude. What a good decision that was. I have left my camper trailer attached to the car...a way of ensuring that I don’t drive today. Anything I do today will be on foot. Perhaps I can find a vanilla slice in the local bakery. A treat while camping.

11.35am

I’ve been for a good walk. I found the bakery and they sold the very best vanilla slice. I asked for it to be cut in half to keep half for later. I consumed it in one go. Then I read one of Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poet[published in a separate volume]. He wrote there: “Do not be bewildered by surfaces. In the depths everything becomes law.” That thought consumed me.

So many people tell me confidently that when they look at a painting it is the surfaces alluded to that matters to them. I sit here by the creek and choose not to be bewildered by the surfaces. I do not want to represent the surface. The longer I sit here the more likely I am to see beyond the surface. The more likely I am to reach for forms of expression that are more than about surface.

So, I began painting. Hoping that nobody came to look, because they would be compelled to tell me that “It doesn’t look like that," and, that their aunty or grandmother is an artist. My mind jumps to Emily Gnawarrye or Peter Newry, and how long they walked the land before they painted anything. Their paintings are not bewildered by the surface. They convey so much more about the land and life.

12.45pm

I have read more of your book. I find myself reading some poems and then revisiting your preface and introduction. You, through Rilke, describe the life that has always been mine. I do not know how I came upon it, but I did. Back in the 70's and early 80's I worked in a therapeutic community in a psychiatric hospital. I became intrigued that when I helped people resolve key events in their lives, so often with tears and deep catharsis, I'd come along the next week and ask how they were feeling. I guess I was looking for the grand affirmation. It wasn't like that. They'd say, "I feel nothing." I'd ask "Would you like/be willing to explore the ‘nothing’?" A pattern emerged over time.

In the nothing, in the void people found life-giving images: water in wilderness, flowers in the desert, light in darkness, order in chaos, life in death; all, it seemed to me, were also Biblical images. Around that time I made a series of paintings that had Jesus falling from the cross into the abyss. (These were painted in 1985 I think. They were destroyed in 2003 when I photographed some of them).

|

| One of Doug Purnell's "destroyed" paintings |

I don't have answers, only questions. As I live the questions the answers begin to emerge in the patterns. I like the sense you pick up in Rilke, that I have not become something or someone; I am always in the process of becoming. Creation comes from a willingness to enter the uncertainty and instability of the void with openness. It is paradoxical. This frightening place that I think might destroy me actually gives me life. Rilke writes and you translate:

I love the dark hours of my being,

for they deepen my senses,

in them as in old letters I find

my daily life already lived

in pious words so soft and subdued.

From them I've come to know that I have room

for a second life, timeless and wide.

As I continue to paint the faces I wonder, intrigued by the truth of the lines:

But You grow into the uncertainty

that lies within the shadow of your face.

And then to wonder how I give voice - or face - to God who is "daily blessing".

I come home from the soaring

in which I’d lost myself.

I was song, and God the rhyme

still rustles in my ear.

I’ll become quiet and simple again,

and my voice will be still,

my face bowed

for a better prayer.

....

I was far off in the place where angels dwell,

High up where light dissolves into the void—

But God darkens in the deep.

I know now that the way forward is in tiny increments, the discipline of returning again and again to the same subject and going deeper, for "God darkens in the deep".

I am delighted to find a new treatment of Rilke here, especially as translated by Mark Burrows. Mark and I first met in New England, so to learn of his work reaching Australia is a delight too. I came across your site looking for Rilke's famous "Christmas letter" to a young poet, and look forward to reading the version given here.

ReplyDeleteIf I may add to the link you also give of Mark's writing, on Christian Bobin - his meditation on Francis of Assisi is another wonderful find, variably titled in translation "The Very Lowly" and "The Secrets of Francis of Assisi."

Thank you William for sharing your pleasure in this Rilke discovery. I regard Mark Burrows as a translator with rare gifts of language and sensibility. You will find more of his translations in my own book on Rilke: In the Company of Rilke, published in the US by Tarcher/Penguin. That book is the only spiritual study of Rilke in English, and is also a study of the experience and power of reading.

DeleteWe will cover Bobin's book on Francis. It's on the list!