I recently read an article on the importance of re-reading, and I have always been an advocate of keeping your favourites on a permament rotation list. Indeed, one of the key elements in the creative writing program I teach is the re-reading of favourite books.

But I find that I only ever do this periodically - normally when I'm ill. When I'm down in the dumps the first thing I do is head for one of my old favourites and go straight to bed. I've never really read them as a corpus of formative influences, back to back.

So, first thing in 2016 I am going to do just that. Sit down and read my ... favourite books all in a row and see just what I discover about myself.

This is my selection, in no particular order:

1. The Pursuit of Love by Nancy Mitford - I have been an ardent Mitfordaphile since I was 14, but this is definitely the crowning glory of all the books. It always makes me laugh and feel happy.

2. Lucia in London by E. F. Benson - Of course, the Lucia books influenced Nancy Mitford quite heavily, and it is because of her that I joined the cult of E. F. Benson. I always think that this is the best of the novels.

3. Oscar Wilde by Richard Ellmann - This is the book that changed my life when I read it at 18. It's quite huge and takes up a lot of time, but it always offers up somjething new and fascinating with each read.

4. The Quest for Corvo by A. J. A. Symons - I find that I recommend this book to people more than any other, and I'm yet to meet someone who didn't love it. Literary mystery, biography and fabulous read.

5. The Gentle Art of Blessing by Pierre Pradervand - I was in Cambodia writing a book when I first read this, and I read it through three times in a row, it was so amazing. Utterly transforming, this has changed the course of my life in so many ways.

6. Peace is Every Step by Thich Nhat Hanh - I was spending a long period travelling around Thailand, having just spent some months in Vietnam staying at monasteries, when I first read this. It affected me so completely that I never really stopped reading it - it is kind of on constant rotation in my life, and I return to it on a weekly basis. It it will be good to read it cover-to-cover again.

7. A Return to Love by Marianne Williamson - Oh, how many memories this brings back! I was young and terribly angry when I got this, but by the third page I was a changed man, and I will be forever grateful to Marianne Williamson for that. I haven't read it in years.

8. Prayer by Philip Yancey - Unexpected, and completely engaging. Another book that changed the way I viewed the world and made me a more thoughtful, and contemplative, human being.

Thursday, December 17, 2015

Wednesday, October 28, 2015

Walter Mason suggests 11 introductory books on Buddhism

Have you ever wanted to learn more about Buddhism but don’t know where to begin?

Most people are shy, especially at first, to just head on down to their local Buddhist temple or centre and start asking questions. Google searches provide us with a bewildering array of choices and sometimes bizarre claims, and often the slickest websites represent the weirdest groups.

Probably the best thing to do is just dedicate some time to reading about Buddhism. Read across a few different schools and traditions to give yourself a real feel for the very diverse landscape of Buddhist thought and practice. And always remember that you don’t have to accept anything just because someone tells you you should. Stay politely questioning, build up a bigger and broader understanding of Buddhism, and then move out into the real world and start exploring Buddhist practice with a community.

Here are some of the best introductory books to Buddhism. It is a personal selection, and is based on years of bookselling, Buddhist practice and recommending books to friends and hearing their feedback.

May you be blessed in your journey!

1. Peace is Every Step by Thich Nhat Hanh – A wonderfully inspiring read, this book is one that everyone would benefit from reading, Buddhist or not. In fact, Master Nhat Hanh has had a profound influence on many non-Buddhist spiritual communities. Simple to read, practical and charming, this is a book that has changed many lives.

2. Start Where You Are by Pema Chodron – This American nun in the Tibetan tradition has become such a beloved writer that I have even heard her name mentioned in mainstream sitcoms. Chodron lead a full, relatively normal, life before she became a nun, and she draws on this as the basis for her teachings. Her books have had a profound effect on many people that I know and respect, and are a terrific read for anyone interested in the spiritual life.

3. The Buddhist Handbook by John Snelling – This is practical, and the sort of thing you use as a reference rather than sit down and read. It is probably the book you have by your side as you are reading the other titles on this list. Nonetheless, it is certainly the best and most exhaustive guide to Buddhist ideas and culture. It has settled many an argument, and I still look at it a few times a year. Invaluable.

4. In this Very Life by Sayadaw U Pandita – A brilliant and no-holds-barred guide to the Burmese meditation tradition, I found this book incredibly liberating when I first read it. It is also a tremendous kick up the bum – reminding us that we don’t have all that much time left on earth, so we’d best start improving ourselves now.

5. Lovingkindness by Sharon Salzberg – A tremendous, beautiful book that I have read many times. Though it comes from a Buddhist perspective (Salzberg is a teacher in the Insight tradition) it has much broader appeal, and is a beautifully written and deeply meditative examination of the Buddhist ideal of lovingkindess. Again, it is one that has been read and loved by Buddhists and non-Buddhists alike and has gained the status of spiritual classic.

6. Discovering Kwan Yin by Sandy Boucher – Buddhist books in English are big on theory and meditative practise, but frequently make no mention of popular traditions of devotion. This can be bewildering for the book-learned Buddhist who travels to Asia and is suddenly confronted by deep levels of devotion that they were unprepared for. Boucher’s book is quite unique in that it discusses practical methods of devotion to Kwan Yin, the Bodhisattva of Compassion, one of the most popular figures in Buddhist Asia. It’s a great book and really very informative. I would also recommend John Blofeld’s older, but still very beautiful and fascinating, The Bodhisattva of Compassion.

7. The Monks and Me by Mary Paterson – A personal memoir of what it’s like to really embrace Buddhism and go away on a long spiritual retreat in a monastic setting. This is the real thing, very honest and very inspiring, It’s about what it’s like to live in a more compassionate way and deal with the cultural shifts that are involved when a Westerner begins exploring Buddhism. And it’s also just a really fun read.

8. The Ground We Share by Robert Aitken and David Steindl-Rast – If you have grown up with a Christian (particularly Catholic) background then you will find this book absolutely fascinating and deeply reassuring. A dialogue between a modern American Zen master (founder of the Diamond Sangha) and a Benedictine monk, this is an examination of the points at which Buddhism and Christianity find common ground and share a mutual regard.

9. The Dhammapada – An official “holy book” of the Buddhist canon, The Dhammpada reads more like what you’d expect religious literature to. It is, in fact, the most famous excerpt from the Pali Canon, the ancient library of Buddhist texts that serves as the beginning point for all of the schools of Buddhism. It is a concise explication of Buddhism, and normally seen as the best explanation of the religious philosophy. It is very brief, but there are some terrible, old-fashioned translations out there which are impossibly dull. Nonetheless, it is essential reading, and is the kind of thing that can be read slowly and meditatively, a passage at a time. These days, I turn to it constantly, and its brevity is really quite brilliant.

|

| Ajahn Tate |

10. The Autobiography of a Forest Monk by Venerable Ajahn Tate – Reasonably obscure in English, it is a constantly fascinating account of what it was like to be a wandering Forest monk in Thailand in the early 20th century. It provides an excellent insight into popular Buddhist belief in the Theravada world, and is a fantastic introduction to popular Thai Buddhism. It is also an engaging read all on its own.

11. The Vision of the Buddha by Tom Lowenstein – A gorgeous, gorgeous little book. Richly illustrated, it is out of print now but you can always find copies on abebooks.com I used to give copies of this as gifts to monks, and they always loved it. An illustrated guide to the Buddhist world, it is educational and, given its size, remarkably exhaustive. If you just read this book alone you would have an excellent idea of the richness and diversity of the Buddhist world and its various schools and philosophies.

Monday, July 20, 2015

Understanding the mysterious country of Bhutan with Jamie Zeppa's Beyond the Sky and the Earth

Ashley Kalagian Blunt reviews one of the few books about the Kingdom of Bhutan.

Renowned as the “Last Shangri-La,” a reputation fuelled by its government’s creation and pursuit of Gross National Happiness, Bhutan has piqued international interest in recent years. The reality of this tiny Himalayan nation is far more complex than glib coverage of GNH can reveal, as Jamie Zeppa’s engaging but at times discomfiting Beyond The Sky and The Earth: A Journey into Bhutan shows.

Zeppa’s memoir is a present-tense account of her two years as an expat teacher in Bhutan. From Toronto, Zeppa has experienced little outside metropolitan North America. Her knowledge of Bhutan comes from black and white photos found in library books – it’s the late 1980s, so her access to further information is limited.

Zeppa conveys a powerful sense of Bhutan’s renowned beauty. At first, the mudslides, the remoteness of her posting, the lack of electricity and the potential for foodborne-illness slow her appreciation of her new home. She writes, “I have done nothing but worry since I arrived in Bhutan, two and a half months ago. … I live in a tiny cramped room of what-if.”

As she connects with her students and neighbours, however, Zeppa begins down a path of deep transformation. The memoir’s most compelling story is her transition from secular Western urbanite to eager student of eastern thought and Buddhist practice. She discovers and practises mindfulness, teaching herself to overcome homesick feelings. She comes to understand that “Buddhist practice offers systematic tools for anyone to work out their own salvation. Here, the Buddha said, you’ve got your own mind, the source of all your problems, but also the source of your liberation. Use it. Look at your life. Figure it out.”

The narrative style eloquently traces her efforts to adjust to cultural quirks that at first she finds unfathomable – such as returning home to find a houseful of guests. Still, she struggles, particularly with the policy of beating students for punishment. “I remind myself that this is not my country, not my education system. … it is part of a bigger cultural system, it involves different values. You can only judge it from your perspective, from your own cultural background and upbringing, and even if you are right, what can you do about it? Back and forth I argue right-wrong, east-west, judgment is possible-impossible.”

This difficulty is magnified when political problems ripple across Bhutan. Zeppa happened to be in Bhutan as the issues between the ethnic-Bhutanese ruling class in the north and the settled Nepali migrant population in the south disintegrated. Eventually, nearly 100,000 ethnic Nepalis were forced out of Bhutan, an instance of ethnic cleansing that is rarely mentioned in news stories touting the Gross National Happiness model. Zeppa describes the difficulty of understanding what is happening around her as the situation becomes more violent.

Throughout the book, Zeppa’s voice matures along with her understanding of Bhutan both as a mythical Shangri-La and as a troubled nation beset by the same challenges of identity and belonging playing out around the world. Zeppa’s ability to interrogate both herself and the culture around her with curiosity and compassion make this book a memorable read.

Ashley Kalagian Blunt is a writer, reviewer and trainer. Originally from Canada, she now lives in Sydney where she is an enthusiastic member of that city's literary underworld. Ashley teaches creative writing, speaking and self-development. She has been published in McSweeney's and the Griffith Review.

Wednesday, July 1, 2015

Greater awareness from Irvin Yalom's classic account of psychotherapy in action, Love's Executioner

Jasmine Rae reviews Irvin D. Yalom's acclaimed examination of life's big topics.

Love's Executioner and Other Tales of Psychotherapy by Irvin D Yalom

Love's Executioner and Other Tales of Psychotherapy was recommended to me by a wonderful person, a counsellor who was offering some group grief counselling which I gratefully accepted after the loss of my beautiful Dad in 2012. I went out and purchased the book straight away but as life goes (at least for me) I didn't actually open it until 18 months later. From that moment I simply couldn't put it down. It felt like gold in my hands, like a portal to my innermost thoughts and fears and a connection to others who felt the same way. The words flowed so easily and somehow humorously across some big topics like life, purpose, relationships, our relationship with ourselves, and the inevitable end of life. It was nothing like I had imagined it to be. I laughed out loud in parts and was hanging on the edge of my seat most of the time. It was honest and in tune with what I had secretly always wanted to talk about, but would rarely allow myself to, for fear of seeming 'negative'.

|

| Irvin D. Yalom |

Irvin D Yalom is a world renowned psychotherapist and author of both fiction and non fiction. Love's Executioner is a tale of 10 patients seeking therapy for similar reasons but at very different stages of life. I could identify with each of the 10 characters on a human level and when learning about their triumphs, I celebrated with them. When reading about their struggles, I cried with them and learned from them. It was also empowering to know that the man writing these discoveries was also very candid about his own struggles with what he labels "existential pain" and "death anxiety." I hope these labels don't scare you away from this book, they are spoken about so openly in these pages that it feels liberating to discuss them and it becomes apparent that nobody is a stranger to them. Knowing that even the most psychologically-equipped of us has their own journey in the same direction as everyone else was very comforting.

After reading Love's Executioner I was more solid in my belief that being aware of my own mortality doesn't make me a morbid person. For me, it makes every day and every lesson after every mistake so much sweeter. I won't get to be on this 'journey' we call life forever. I also won't always have the opportunity to possess this vessel (my little 4 ft 9 inch body) to get around in, to see things, to meet people, to READ, and create. So there's no better time to do the things I've always wanted to do… right now… while now is still mine for the taking.

About the reviewer:

Jasmine Rae is one of Australia's most acclaimed country music artists. She has toured all over Australia and overseas. She has had many #1 singles in the Australian country music charts and has been nominated for Aria and Golden Guitar awards. Her latest album is Heartbeat.

Sunday, May 31, 2015

Inspired by Julia Cameron's memoir of a writing year, The Creative Life

Walter Mason reviews Julia Cameron's charming account of a year of creative frustration in New York City.

“I’m sixty-one years old, a veteran writer, I still get scared, and I am safe.”

|

| Julia Cameron |

Julia Cameron has become such a sage for so many writers that almost anything she writes about writing becomes an instant classic. The same goes for The Creative Life, her 2010 diary of a year spent struggling with writing and meeting with and encouraging more creatively productive friends. There is something meta about the book in that she describes the process of writing the book you are reading and how it came to take its present form. It is a book about not being able to write a book, and this book is the finished product. And as such it is totally fascinating.

Cameron’s life is filled with creative people doing amazing things, some famous and some less so. She writes enthusiastically, for example, about her brothers new CD and her pride in his musical accomplishments. She describes his humble pleasure in her praise, reminding us all that our encouragement of other creative people is always needed, though it might only be hastily noted. Though the recipient may be shy or embarrassed, one’s words of praise always have an effect.

I remember years ago reading about her idyllic life in Taos, New Mexico. But in this book it becomes clear that Taos was to become a place of sorrow for Cameron, the site of a creative and mental breakdown so serious that she feels she can never return there. An enthusiastic old friend comes to New York City and urges her to re-visit:

“"Taos has become a writer’s mecca,” he tells me. He describes the new café and coffee bar that is ideal for writing. “You’d love it,” he concludes, knowing that I made a habit of writing in Dori’s bakery, now defunct.”

Here we are in thorough Cameronian territory – going outside to write, being in the world and an observer of the world. This is what the whole of The Creative Life is about: turning one’s own life into “material.” She renders the quotidian delicately poignant, occasionally remarkable and always fascinating. This is what makes her such an extraordinary writer and not just another self-help guru with a couple of good ideas. And the ideas keep popping up in this book, though it is in no sense intended to be a practical manual of writing tips. They emerge through the course of her description, and are often attributed to other people (a hallmark of Cameron’s honesty, integrity and generosity). Having attended a wonderful concert of American song, her flatmate and composer friend says:

“That is what I’m meant to be doing,” Emma whispers excitedly as we file out: “I think I should write ninety songs in ninety days again.”

“Maybe I’ll join you at that,” I respond.

Ninety songs in ninety days! A wonderful idea, though I will probably never write a song, not having the skills. Still, it caused me to take up my notebook and scribble down the possible alternatives: ninety blog posts in ninety days, ninety essays in ninety days, ninety poems in ninety days or even, most ambitiously, ninety chapters in ninety days. It is the idea of such self-encapsulated, easily grasped projects that is so stimulating to the creative mind, and it is Cameron’s genius that she recognises this. Putting a time limit and quantity on something works like magic, just as the length and structure of a novena inspires those wanting to pray more.

The experience of ageing is, Cameron suggests, is one that doesn’t diminish our creative capacities but instead increases them:

“Plainly, Tracy doesn’t like “taking it easy.” I remember her cantering through the woods in Central Park. I remember her flying through traffic on her roller skates. It occurs to me that Tracey must hold similar images of me. I no longer own a horse, and I no longer roller-skate. Tracy and I hold each other’s daredevil history. Our adventures now are artistic, not physical.”

The Creative Life is a terrific read, from beginning to end, and one of those rare books that I felt I always had to run back to in order to read just one more page. It is a book about friendship, eating, meeting others and looking for creative stimulation on the work of others. It is about the art of conversation and how more successful companions should be inspirations rather than sources of envy. It is a book about what inspires and how to allow yourself to be inspired, and a wonderful antidote to some of the cynicism of this occasionally confusing existence.

Saturday, May 30, 2015

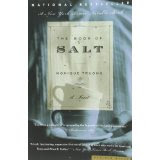

Discovering the brilliant novel, The Book of Salt by Monique Truong

Dr Stephanie Dowrick reviews Monique Truong's

quite brilliantly imagined novel, The Book of Salt

How fortunate we are in this Book Club that we are not locked in to reviewing the "latest". Our freedom is to review what we are currently excited about and that certainly describes my response to Monique Truong's quite brilliantly imagined novel, The Book of Salt.

It was recommended to me some time ago by Walter Mason, my co-host here on this book club website, and I bought it immediately but then let it sit for some time on my shelves until I was traveling and could give it the attention he assured me it would deserve. And it does! Oh, indeed it does. The novel is enchanting and immensely skillful. It evokes a most fascinating time (Paris in the 1930s) with strongly evocative glimpses back to a Vietnam occupied by the French where our narrator, Binh (though that is not his real name), was never going to fit.

|

| 1930s Vietnam |

Many readers will be attracted to this novel to know more about the quite fascinating Stein and Toklas. They will get that in plenty. And they will be given and will "get" the uneasy decade that preceded the "impossible" Second World War. But what few readers will predict is the pitch-perfect portrait of Binh. Servants - like Binh - are valued, but always conditionally and highly superficially. If their work is not "up to scratch", they cease to exist as valued people. The images of exile flow through this novel like incoming tides. Binh is homosexual (long before anyone was "gay"). The risks of this, especially for an "Asiatique" who was neither wealthy nor valued for anything but his culinary talents, made him almost as vulnerable in Paris as he has been in Vietnam.

Truong writes like a poet but tells stories like a master. She never lets the reader go; she never abandons or sentimentalises Binh. In an interview a few years ago she was asked about how she builds character. Her reply:

I begin with a character who fascinates me. I focus first on that character’s voice. Reading aloud is a large part of my writing process because I want to “hear” my characters. So far, I’ve written novels only in the first person voice. I don’t see that changing. I like the limitations of the first person voice. I like working within the restrictions of a particular character’s vocabulary and emotional range or lack thereof. I’m also a firm believer that for every story there are many other versions of that story that are not being told. The first person voice, for me, is all about highlighting that sharing and withholding.

The story of Binh that Truong tells - no, brings fully to life - is a story rarely told. The creative playfulness of pitching this next to the story of Stein and Toklas - over-feted, over-valued, at least in literary terms - takes nothing from the seriousness of this writer's intent, nor from the immense satisfaction of reading her exquisite novel. The blurb for The Book of Salt also draws our attention to the walk-on roles of Paul Robeson and the very young Ho Chi Minh. But it's the life that Truong gives to the invisible Binh and to all the countless and uncounted other Binhs that moved me most. Brilliant? Yes.

Dr Stephanie Dowrick co-hosts this book club and is herself a widely published writer. Please consider using our book store links to give a small returning % to us for admin. (All our reviews are voluntary.) The direct link for this book is HERE. Your comments are welcome. You can find Stephanie and also Walter Mason on Facebook. They also both blog on their own websites and contribute widely to the media.

Monday, April 20, 2015

A fascinating slide between fact and fiction: Ashley Kalagian Blunt reviews HHhH

I started HHhH with skepticism. A publisher had recommended it to me, with an implied ‘if your work was more like this …’ An early rejection I’d received had likewise included a recommended title, but I’d found that one unreadable.

Laurent Binet’s debut novel, in contrast, compelled me to read straight through. In short, it’s the true story of the assassination attempt on Reinhard Heydrich, chief of the Nazi secret services, by two Czechoslovak resistance fighters in 1942. The book is marketed as a novel – as fiction – but aside from a few imagined scenes based on as much historical fact as could be acquired, it is very much non-fiction. Binet ensures readers are aware of that by writing himself into the story. He creates a parallel narrative in which he depicts the struggle to keep this history alive as it was.

|

| Reinhard Heydrich |

|

| Laurent Binet |

Binet works to draw every scene, every bit of dialogue in HHhH from historical records. As narrator, he reveals his obsession for bringing history to life through passionate attention to minute detail – was the colour of Heydrich’s car black or dark green? And does this matter? – and he delivers all this with a keen sense of story. Binet weaves the threads of characters’ – peoples’ – lives with driving force.

So we have the story of Heydrich, the man who, of all those in the Nazi hierarchy, was the one to oversee the bureaucratic creation of ‘the Final Solution.’ We have the assassination attempt on Heydrich (and if don’t already know how it turned out, I won’t spoil it for you; Binet builds the assassination to a sharp climax). We also have the story of the narrator, the author, who has researched his heroes and villains with equal diligence and cheers on his heroes with admiration and affection. Binet compares the heroes of his book to fictional heroes, concluding they ‘are less scrupulous … because they are real people, both greater and more flawed than any fictional character.’

Throughout the book, Binet comments on his own writing – informing readers which details are wholly accurate, which ones he had to guess at, and why, if he had to guess, he felt they should be included. This style of writing might drive some readers crazy – they might wish to experience the story (historically accurate or not) without the author constantly interrupting. Perhaps it’s because I’ve battled some of these same issues in my own writing that I find Binet’s explanations, qualifications and hypotheses so fascinating. But I think I would appreciate Binet’s work regardless. It’s like being invited to watch a play from backstage, or to view the complex, mysterious innards of a jet engine. These inner workings make the experience more intimate.

The short chapters of HHhH help to create its fast pace. The 257 chapters are on average less than two pages each (which is likely why the book contains no page numbers, an inconvenient formatting style despite the short, numbered chapters). The narrator struggles to understand his book even as it is rushing forward. By chapter 205, he states, ‘I think I’m beginning to understand. What I’m writing is an infranovel’ – by which he seems to mean a novel that allows us to peer into the black hole of history. Note that these two sentences make up all of chapter 205 – and still, it’s not the shortest chapter.

Binet cares so deeply for his story, particularly for its heroes, that he occasionally slips into imagining himself alongside them, or even as them. As he says, for him this story is personal. He allows himself into his heroes’ narrative only momentarily, but works to bring us closer to the characters and Binet, as well as his struggle to represent them. In his dramatic final scene, when it’s clear the resistance fighters can’t escape the SS soldiers who come for them (and though Binet reveals this outcome in the early pages of the book, this climax is still full of drama), Binet pauses to imagine a different ending for them. It’s this complex relationship between Binet and his story that make HHhH a powerful book.

About the reviewer

|

| Photo by Robert Srjararian |

Thursday, March 19, 2015

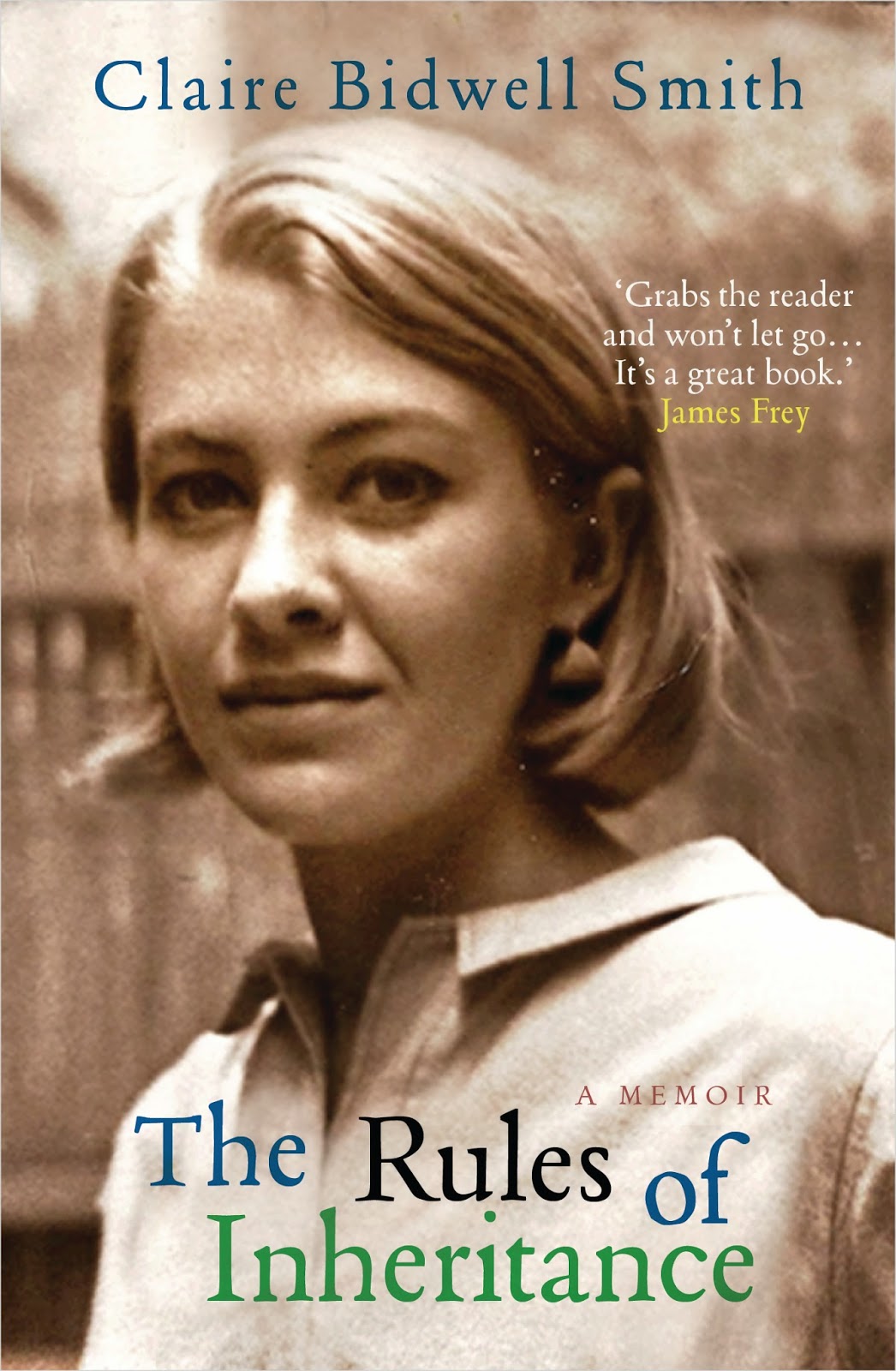

A liberating understanding of grief: Stephanie Dowrick on The Rules of Inheritance

Can there be anything more difficult to experience - or write about - than profound grief? I'd say not. It was the theme of my own first novel, Running Backwards Over Sand. It is also, and more directly, the theme of Claire Bidwell Smith's immensely accomplished memoir, The Rules of Inheritance. In this book she writes not just about the death of one parent, relatively early in life, but two. An only child of her parents' devoted marriage, her "aloneness" is overwhelming. It is the aloneness of loss; it is also the very specific gnawing isolation of seemingly everlasting grief.

Smith uses a non-linear but highly persuasive structure to tell her story of love, regret, shame, tenacity, foolishness, courage and insight. In less skilled hands, this could be distracting. Smith, though, is a natural story-teller. We can trust her as a writer in ways she clearly did not trust herself for many years. Her long, winding, patchy road to living fruitfully and positively is immensely recognizable in its very patchiness and her structure - which is totally within her command - supports this. Comprehension, awareness, an increase in consciousness: these all take time, commitment and a surrender to story in the deepest meaning of that word.

How do we contract, expand; construct, destruct; investigate, know? None of this is achieved through the conscious mind only which is in part why an account of grief as accomplished and as persistent as Smith's will be of such value to so many readers. "There isn't a right way to grieve," she writes. And, soon after, "But if you haven't been through a major loss, the the truth is that you just don't know what to say to someone who has." Grief takes one to a different country. Abandoned there - not least by the absence of the person or people you are grieving - many of us behave in ways that may later shame us. Recklessness is often part of a grief story, especially among the young. It was certainly part of my own story and in Smith's persistence with dangerously unhealthy relationships, and the depression that never cleared even while she studied, worked, lived and even loved, many readers will see themselves.

Here is a writer forced by the depth of her intelligence as well as her losses to understand not just her own grief, but grief itself. That understanding is of real service to us all, to all who are brave enough to love fully...to know and not avoid knowing that death is part of love as well as essential to physical existence.

I am filing this review from my iPad, with all the restrictions of this otherwise handy little tablet. I will add images when back at my desk (now done!). But my message is clear. I am moved by this book. I am deeply moved by the author's hard won insights and the depth of her commitment in bringing them to the page. My impulse to write this review before returning to my office in a couple of weeks is two-fold. Perhaps it is the very book that will be the companion you need; it is a companion. And also, and more personally, I have been thinking a great deal about my Writers' Workshop class of 2014, some of whom are newly engaged in deep memoir writing. There is, for them and other writers, much to gain and learn here about the "piecing" together of anyone's story. In that, and in so many other ways, The Rules of Inheritance opens up for us some of the...not rules, but experiences that enable healing, connection, understanding. It is always Claire's story; in its depth and breadth of emotion and enquiry, it is - in moments and parts enough - also ours.

|

| Claire Bidwell Smith |

About the reviewer

Dr Stephanie Dowrick is the author of many books including Seeking the Sacred and Forgiveness and Other Acts of Love. She teaches writing for the Faber Writing Academy in Sydney and co-hosts this Book Club. You can comment on her public Facebook page, or follow her there for inspirational teachings. The Rules of Inheritance is available POSTAGE FREE from this LINK.

Sunday, February 22, 2015

How to Stay Married: A deliciously honest look at travel, marriage and the romantic requirements of a new era

This is a fascinating book, an at times alarmingly candid memoir of courtship and marriage in later life framed around a long and relationship-challenging holiday around the world. It begins with an open letter to all of those who have a desire to find a partner, and the author Mary-Lou Stephens wants you to know that once a man (or woman) is in the house, the really hard work is just beginning. “Relationships that last are not easy,” she counsels. “Getting to the place where you feel safe and happy is a journey.”

And How to Stay Married is an account of one such journey. Many of you will know Mary-Lou’s work from her previous memoir, a truly exceptional account of spiritual awakening called Sex, Drugs and Meditation. That is one of my very favourite books of recent years, and this follow up is a very satisfying work indeed for anyone who enjoys her confessional style and gentle, honest wisdom.

At the outset we are warned that this will be a book that pulls no punches in discussing the fallibility of human relationship, particularly when it is romantic and sexual in nature. Mary-Lou confesses to being a rule follower but secret resenter, and this passive-aggressive capacity (one at which Australians, myself included, excel) is turned on her hapless husband who bungles travel arrangements and is too confident in his own abilities. It begins the round of revealing stories that need to be read occasionally rough one’s fingers – is she really saying that about her husband? Has he read the book? It makes for a compelling and utterly absorbing read. (And, for the record, he has read the book, and gave the author complete carte blanche to say whatever she wanted to about their relationship).

|

| Mary-Lou Stephens |

Mary-Lou pulls no punches in depicting the unusual suite of anxieties we bring to our romantic endeavours in the 21st Century. How to refer to one’s relationship, for example. He hated to be “the boyfriend’ and she hated the ambiguity of “my partner,” and so marriage became a way to resolve linguistic worries. And then there’s the question of desire, or at least its direction. On first meeting her future husband she had mistakenly assumed he was gay, and so almost missed the opportunity to connect with her life partner.

At one point in this book the author and her husband go to spend some time at the famous Findhorn spiritual community in Scotland. This place, famous for its nature spirits and giant cabbages, is brilliantly evoked by Stephens as she recounts the blandness of a communal setting, and the unexpected jealousies and annoyances that pop up just when she was hoping to be at her most spiritual. There’s a neurotic American woman flirting with her husband, for example, and neither of them can bear the bland vegetarian fare on offer.

|

| Findhorn community, Scotland |

It is Mary-Lou Stephens’ eye for detail and her capacity to call out pretension that make her such a brilliant chronicler of modern living. And her-real-word dilemmas and contradictory calls remind us of ourselves as we read. Despite her general lack of enthusiasm, for example, about the realities of Findhorn, she finds herself fantasising about living there, and becoming a whole different kind of person. Anyone who has done a residential spiritual retreat will recognise these fantasies that spring forth in moments of enthusiasm, usually coupled with matching episodes of anger and contempt.

What makes How to Stay Married so special, and so very engaging, is its author’s ability to capture and really speak out loud the things that plague us about establishing a long-term partnership with another flawed human being. As more and more of us find ourselves single in our later years, we have to confront the awkwardness of learning to make new compromises long after we have settled into our own ways. Mary-Lou occasionally resents her husband’s wildly confident pronouncements on diverse subjects, for example. And occasionally she gets furious at his own spark of independence, along with his rather hopeless approach to personal finances. I defy anyone to read the book and not experience a twinge of recognition and guilt when she describes some unsatisfying example of her flawed but very real partnership.

Mary-Lou is good, too, at describing the simpler, almost primal comforts of being in the company of another person more or less constantly. Her new husband is physically unlike other men she has been with, and this new experience still occasionally surprises and delights her:

“I’m also thankful for being the wife of a big man. Big in stature, in girth and in spirit. I am safe in the company of strangers, in a rough working class pub, with this man beside me.”

Ultimately this exquisite book is a testament to the great folly of romantic engagement with another human being. Yes, such adventures are unequal, wildly frustrating and even, occasionally, soul-wounding. Our partner does become our mirror, in which we can begin to recognise those qualities, good and bad, that make us so unique. How to Stay Married is a book of great humanity, and it is unique in its willingness to speak the complete truth about the pressures of companionship. One to read for anyone who has ever been, or wanted to be, married.

Wednesday, February 4, 2015

Sheridan Rogers walks in Rilke's footsteps

Who, if I cried out, would hear me among the angels’

hierarchies? and even if one of them pressed me

suddenly against his heart: I would be consumed

in that overwhelming existence. For beauty is nothing

but the beginning of terror, which we still are just able to endure,

and we are so awed because it serenely disdains

to annihilate us. Every angel is terrifying.

- The First Elegy, Rainer Maria Rilke (Stephen Mitchell trs.)

Sydney writer Sheridan Rogers reflects on a recent visit to Duino Castle, near Trieste, the very place that inspired the "Duino Elegies", arguably Rilke's greatest contribution to 20th-century poetry and life. She also reflects on her own relationship to this poet and his work.

"Great art often communicates before it is understood..."

“Be patient toward all that is unsolved in your heart and try to love the questions themselves, like locked rooms and like books that are now written in a very foreign tongue.

“Do not seek the answers which cannot be given you because you would not be able to live them. And the point is, to live everything. Live the questions now. Perhaps you will then gradually, without noticing, live alone some distant day into the answer.”

Silent friend of many distances, feel

how your breath enlarges all of space.

Let your presence ring out like a bell

into the night. What feeds upon your face

Grows mighty from the nourishment thus offered.

Grows mighty from the nourishment thus offered.

Move through transformation, out and in.

What is the deepest loss that you have suffered?

If drinking is bitter, change yourself to wine.

- Sonnets to Orpheus 11, 29

For this suffering has lasted far too long;

none of us can bear it; it is too heavy -

this tangled suffering of spurious love

which, building on convention like a habit,

calls itself just, and fattens on injustice.

Show me a man with the right to his possession.

- Requiem

Oh how I yearned for a soul mate like Rilke, someone with his depth and insight. And here he was, in Requiem, again speaking directly to me:- Requiem

Are you still here? Are you standing in some corner? -

You knew so much of all this, you were able

to do so much; you passed through life so open

to all things, like an early morning.

For this is wrong, if anything is wrong:

not to enlarge the freedom of a love

with all the inner freedom one can summon.

We need in love, to practice only this:

letting each other go. For holding on

comes easily; we do not need to learn it.

- Requiem

|

| Rainer Maria Rilke and Clara Westhoff |

Ah, I found myself asking, had he - the "Poet Rilke" - also cast his spell over me? Dowrick continues: “Rilke’s not-so-private life is certainly not above moral discussion. On the contrary, some critics have spun years of work out of exactly that. Yet anything but a glance in Rilke’s direction shows that the paradoxes around him are extreme.”

Dowrick quotes another poet, Galway Kinnell, from his book The Essential Rilke: “A number of readers and critics...reverse the conventional wisdom – that an artist’s human deficiencies, as well as any attendant human wreckage the artist might leave behind, are simply the price that must be paid for great art – and find that certain often-dismissed flaws in fact damage the art. These more sceptical readers see Rilke less as an authority on how to live than as a sufferer telling in brilliant confusion his own strange and gripping interpretation of what it is to be human.”

How we squander our hours of pain.

How we gaze beyond them into the bitter duration

to see if they have an end. Though they are really

our winter-enduring foliage, our dark evergreen,

one season in our inner year --,not only a season

in time--, but are place and settlement, foundation and soil and home.

- The Tenth Elegy

|

| Duino Castle - "Who, if I cried out, would hear me...?" |

The Castle is set on an imposing rock spur of the Carso high above the Gulf of Trieste, and the vivid contrast between the sheer brilliant white of the limestone cliffs and the deep cobalt blue of the Adriatic Sea left me gasping – as had the Elegies. After all these years, here he was calling to me again:

Children, one earthly Thing

truly experienced, even once, is enough for a lifetime.

Don’t think that fate is more than the density of childhood;

how often you outdistanced the man you loved, breathing, breathing

after the blissful chase, and passed on into freedom.

Truly being here is glorious.

- The Seventh Elegy

The old castle is now a ruin and is famous for the legend of the Dama Bianca (the White Lady) because the white rock on which the castle sits is said to have the shape of a veiled woman.

The legend tells of a White Lady thrown from the walls of an ancient castle by her wicked husband, but the sky felt pity for her and gave her a rock body before she fell, smashing onto the rocks. It is said her soul is still there on a cliff near the remains of the old castle and that some nights she comes to life again and wanders restlessly.

But if the endlessly dead awakened a symbol in us,

perhaps they would point to the catkins hanging from the bare

branches of the hazel-trees, or

would evoke the raindrops that fall onto the dark earth in springtime. --

And we, who have always thought of happiness as rising, would feel

And we, who have always thought of happiness as rising, would feel

the emotion that almost overwhelms us

whenever a happy thing falls.

- The Tenth Elegy

- The Tenth Elegy

There was no tempest the day I visited. As I stood with the clear autumn sunshine on my back and looked through the dark woods to the old castle and out to the wide blue sea, I recalled his words:

Nowhere, Beloved, will world be but within us. Our life

passes in transformation. And the external

shrinks into less and less....

Many no longer perceive it, yet miss the chance

to build it inside themselves now, with pillars and statues: greater.

- The Seventh Elegy

|

| Sheridan Rogers |

Sheridan Rogers is a Sydney writer currently living in Italy. You can contact her via her blog or also via Facebook. You can purchase the books mentioned POSTAGE FREE via the links provided or via the bookstore links above right. We have had several articles on Rilke over the years - not least because of Stephanie Dowrick's and also Mark S Burrows' interest and scholarship on the poet. Please put "Rilke" into our search button and find those treasures! Sheridan's Rilke extracts are from Stephen Mitchell's translations of Rilke's work.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)