|

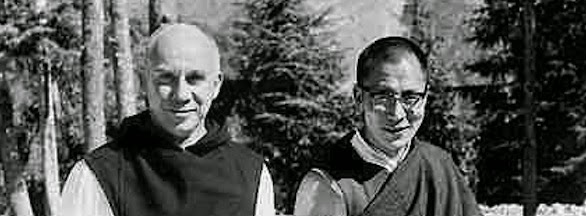

| Thomas Merton and the young 14th (current) Dalai Lama |

Peace activist Father John Dear wrote the powerful article that follows for Hiroshima Day, 2005, reflecting on the peace-making activism of monk and writer Thomas Merton (who died in 1968) - and the “Wisdom of Nonviolence”. Through the marvels of web researching, I (Stephanie Dowrick) “fell upon it” while looking for a more general Merton reference. It's an article I regard as essential reading for us all. Almost ten years later, John Dear continues his peace activism work and you can learn more about it at his website. We thank him for his permission to reproduce the article here.

If you agree that this article is worth your time and thought, please consider how you can use social and other media to circulate it, not because you need to agree with every point raised, or every point that Merton himself made, as a man of his time, but because this article richly contributes to one of the most fundamental and urgent discussions of our time.

Peace is, I believe, our greatest challenge as a human family.

If you agree that this article is worth your time and thought, please consider how you can use social and other media to circulate it, not because you need to agree with every point raised, or every point that Merton himself made, as a man of his time, but because this article richly contributes to one of the most fundamental and urgent discussions of our time.

Peace is, I believe, our greatest challenge as a human family.

If we fail to create the necessary changes in our personal and collective thinking about how best to live alongside one another in peace and safety and with mutual respect, we will fail in everything. We will fail ourselves; we will certainly fail the generations to come.

We can, we must think intelligently and deeply together about alternatives to the delusion that war is an arguable “solution” to human problems, that increased conflict is an acceptable path to peace, or that we can achieve personal happiness while so many in our world suffer conflict and its vast attendant miseries, including homelessness, starvation and despair.

We need to release ourselves from the pessimism that runs deep in our culture, whispering to us that there will always be wars (in our homes, on our streets, between tribes and nations).

Merton calls us - whatever our faith, culture, “beliefs” - to become “contemplatives, students, teachers, apostles, visionaries, instruments, prophets of non-violence”. I hear that as a call to love far more and far less conditionally; to be far bolder in our hopes for our world and one another; to achieve the safety, wellbeing and peace we are, now, daring to imagine. Could anything matter more?

God of peace, writes John Dear, we are blind. Give us the vision of peace to see every human being on the planet as our sister and brother, to love our neighbors and our enemies, to learn like Merton, that in the end, we are all one in you. Amen, we say. And again, Amen.

God of peace, writes John Dear, we are blind. Give us the vision of peace to see every human being on the planet as our sister and brother, to love our neighbors and our enemies, to learn like Merton, that in the end, we are all one in you. Amen, we say. And again, Amen.

|

| Thomas Merton |

John Dear: Thomas Merton and the Wisdom of Nonviolence

San Diego, California

Like all of you, Thomas Merton has been one of my teachers, and it's a blessing to reflect on his exemplary life and astonishing witness.

I'm 45, have been in the Jesuits almost 25 years now, went to college at Duke University, decided one day that I really did believe in God and that I wanted to give my whole life to God, and the next thing you know, I was entering the Jesuits. I'm still trying to figure out how that happened! Before I entered the Jesuits, I decided I better go see where Jesus lived, so I decided to make a walking pilgrimage through Israel, to see the physical lay of the land, only the day I left for Israel in June 1982, Israel invaded Lebanon and I found myself walking through a war zone.

By the end of my two-month pilgrimage, I was camping around the Sea of Galilee, and visited the Church of the Beatitudes, where I read on the walls: "Blessed are the poor, the mournful, the meek, those who hunger and thirst for justice, the merciful, the pure in heart, the peacemakers, those persecuted for the sake of justice, and love your enemies." I was stunned. I walked out to the balcony, looking out over the Sea of Galilee, and asked out loud, "Are you trying to tell me something? Okay, I promise here and now to dedicate my life to the Sermon on the Mount, to promoting peace and justice, on one condition: if you give me a sign." Just then, several Israeli jets fell from the sky breaking the sound barrier, setting off a series of sonic booms, coming right toward me. After they flew over me, I look backed up at heaven, and pledged to live out the Sermon on the Mount and never ask for a sign again!

When I entered the Jesuits three weeks later, I was on fire with a desire to pursue the life of peace and justice. I started to study the writings of the great peacemakers, such as Gandhi, Dr. King, Dorothy Day, the Berrigans and, from day one, Thomas Merton. Like you, I've been reading Merton ever since. I think I've read everything he's published, and I'm amazed how he still speaks to me. In contrast to the culture, to the TV, to the President, even the whole world, Merton remains a voice of sanity and reason and faith and clarity and hope, and I can't put him down.

I don't know if you heard what the great theologian David Tracy recently said when he was asked what the future of theology in the U.S. would look like. He answered spontaneously, "For the next 200 years, we'll be trying to catch up with Merton."

In 1989, I visited the Abbey of Gethsemani for the first time, and became friends with Br. Patrick Hart. Later, when I was in prison for nearly a year for a Plowshares disarmament action, Brother Patrick, wrote that Gethsemani wanted to support me, and he offered to let me stay for a while in Merton's hermitage, which was one of the great experiences of my life. I later published my journal from my retreat there called, The Sound of Listening. Later, again, I went back for another long stay. It was one of the greatest blessings of my life to live and pray in Merton's hermitage.

Over the years, Merton has helped me not only in my work for peace but in keeping me in religious life and the church because whenever I get in trouble for working for peace and justice, or whenever I get discouraged about the church or religious life, I recall how much trouble Merton was in for writing about war, racism, nuclear weapons and monasticism, how he stayed put, remained faithful, did what he could, said his prayers and carried on, so I take heart from Merton because he endured it all with love, with a good heart, and now we see how his life and sufferings and fidelity have born great fruit. I think we can all find new strength and courage from him to carry on and be faithful in our service to the God of peace.

When I think of Merton's "Revelation of Justice and Revolution of Love" (the theme of our conference) and what Merton has taught me, I return once again to the wisdom of nonviolence. So I would like to share five simple callings that I have learned from Thomas Merton.

First, Merton invites us to become contemplatives, mystics, of nonviolence.

Merton's whole life was based on prayer, contemplation and mysticism, but it was not so that we could go and hurt others, or bomb others, or dominate the world, but so that we could commune with the living God. I spent my first ten years as a Jesuit praying by telling God what to do, yelling at God for not making the world a better place, until finally, a wise spiritual director said, "John, that is not the way we speak to someone we love." A light went on in my mind: prayer is about a relationship with someone I love, with the God of love and peace. So my prayer changed to a silent listening, a being with God, which is what contemplative nonviolence is all about.

Merton knew that prayer, contemplation, meditation, adoration and communion mean entering into the presence of the God of peace, dwelling in the nonviolence of Jesus, that, in other words, the spiritual life begins with contemplative nonviolence, that every one of us is called to be a mystic of nonviolence.

So, in prayer, we turn to the God of peace, we enter the presence of the One who loves us and who disarms our hearts of our inner violence and transforms us into people of Gospel nonviolence and then sends us on a mission of disarming love and creative nonviolence.

Through contemplative nonviolence, we learn to give God our inner violence and resentments, to grant clemency and forgiveness to everyone who hurts us; to move from anger and revenge and violence to compassion, mercy and nonviolence so that we radiate personally the peace we seek politically.

In the end, as Merton knew, peace is a gift from God. If we are addicted to violence, as the Twelve- Step model teaches, we need to turn to our Higher Power, confess our violence, support one another through communities of nonviolence, and become sober people of nonviolence. "The chief difference between violence and nonviolence," Merton writes, "is that violence depends entirely on its own calculations. Nonviolence depends entirely on God and God's word." ("Blessed are the Meek," in The Nonviolent Alternative, Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, New York, 1971.)

When Jesus calls us to love our enemies, he said we should do so because God does so. God lets the sun shine on the just and the unjust and the rain fall on the good and the bad. God is compassionate to everyone, and we should be, too. This is the heart of contemplative nonviolence. Then we are able to see everyone as a human being, and to see God and become like God.

As we pursue contemplative peace like Merton, we learn, contrary to what the Pentagon tells us, that our God is not a god of war, but the God of peace; not a god of injustice, but the God of justice; not a god of vengeance and retaliation, but the God of compassion and mercy; not a god of violence, but the God of nonviolence; not a god of death, but the living God of life.

We discover a new image of God. As we begin to imagine the peace and nonviolence of God, we learn to worship the God of peace and nonviolence and, in the process, become people of peace and nonviolence.

"The great problem is this inner change," Merton writes. "We all have the great duty to realize the deep need for purity of soul that is to say, the deep need to be possessed by the Holy Spirit."

On his way to Asia, Merton told David Stendl-Rast that, "The only way beyond the traps of Catholicism is Buddhism." In other words, every Catholic has to become a good Buddhist, to become as compassionate as possible, he said. "I am going to become the best Buddhist I can, so I can become a good Catholic."That is the wisdom of Merton's contemplative life, to become like Buddhists, people of profound compassion, deep contemplative nonviolence.

That is what he discovered with his experience in Polonnaruwa when he wrote: "Everything is emptiness and everything is compassion."This is what Merton meant when he wrote about Gandhi: "Gandhi's nonviolence was not simply a political tactic which was supremely useful and efficacious in liberating his people. On the contrary, the spirit of nonviolence sprang from an inner realization of spiritual unity in himself. The whole Gandhian concept of nonviolent action and satyagraha is incomprehensible if it is thought to be a means of achieving unity rather than as the fruit of inner unity already achieved." (Gandhi on Nonviolence, New Directions, New York, 1964).

So Merton calls us to be contemplatives and mystics of nonviolence, instruments of the God of peace.

Second, Merton teaches us to become students and teachers of nonviolence.

Merton was not just a great teacher, but the eternal student. He was always studying, always learning, always searching for the truth. So when he started reading Gandhi in the 1950s and then meeting peacemakers like Daniel Berrigan and the folks from the Fellowship of Reconciliation and the Catholic Worker, he became a student and teacher of Gospel nonviolence, and I think that's what each one of us has to do: to study, learn, practise and teach the Holy Wisdom of nonviolence.

The lesson starts off with the basic truth: Violence doesn't work. War doesn't work. Violence in response to violence always leads to further violence. As Jesus said, "Those who live by the sword, will die by the sword. Those who live by the bomb, the gun, the nuclear weapon, will die by bombs, guns and nuclear weapons." You reap what you sow. The means are the ends. What goes around comes around.

War cannot stop terrorism because war is terrorism. War only sows the seeds for future wars. War can never lead to lasting peace or true security or a better world or overcome evil or teach us how to be human or as Merton insists, deepen the spiritual life.

|

| Thomas Merton with the young Thich Nhat Hanh |

In a spirituality of violence, the church rejects Jesus and the Sermon on the Mount as impractical, takes up the empire's just war theory, launches crusades and blesses Trident submarines and remains silent while Los Alamos churns out nuclear weapons and enjoys the comforts of the culture of war and injustice rather than taking up the cross of Gospel nonviolence. We have a private relationship with God, fulfill our obligations and go right along with the mass murder of our sisters and brothers around the world.

The empire wants the church to be indifferent and passive; to be divided and fighting and silent, even to bless wars and injustice.

Unless we speak out and teach the wisdom of peace and nonviolence, the church will become like Hazel Motes' church in Flannery O'Connor's book [of short stories] Wise Blood, the "Church Without Christ", where the lame don't walk, the blind don't see, the deaf don't hear, and the dead stay dead. That's what Merton learned.

The wisdom of nonviolence teaches that: War is not the will of God. War is never justified. War is never blessed by God. War is not endorsed by any religion. War is the very definition of mortal sin. War is demonic, evil, anti-human, anti-life, anti-God, anti-Christ. For Christians, war is not the way to follow Jesus. "The God of peace is never glorified by human violence," Merton wrote. In other words, peaceful means are the only way to a peaceful future and the God of peace.

So like Merton, we have to study nonviolence, define it, talk about and think about how each one of us can become more nonviolent, and how we can create a church of nonviolence, even a new world of nonviolence. So Merton studies it and concludes: "What is important in nonviolence is the contemplative truth that is not seen. The radical truth of reality is that we are all one."(Blessed are the Meek)

Merton's nonviolence begins with the vision of a reconciled humanity, the truth that all life is sacred, that we are all equal sisters and brothers, all children of the God of peace, already reconciled, all already united, and so, we could never hurt or kill another human being, much less remain silent while our country wages war, builds nuclear weapons, and allows others to starve.

So nonviolence is much more than a tactic or a strategy; it is a way of life. We renounce violence and vow never to hurt anyone again. It is not passive but active love and truth that seeks justice and peace for the whole human race, and resists systemic evil, and persistently reconciles with everyone, and insists that there is no cause however noble for which we support the killing of any human being; and instead of killing others, we are willing to undergo being killed in the struggle for justice and peace; instead of inflicting violence on others, we accept and undergo suffering without even the desire to retaliate as we pursue justice and peace for all people.

Nonviolence is active, creative, provocative, and challenging. Through his study of Gandhi, Merton agreed that nonviolence is a life force more powerful than all the weapons of the world, that when harnessed, becomes contagious and disarms nations. So nonviolence begins in our hearts, where we renounce the violence within us, and then moves out with active nonviolence to our families, communities, churches, cities, our nation and the world. When organized on a large national or global level, active nonviolence can transform the world, as Gandhi demonstrated in India's revolution, or as Dr. King and the civil rights movement showed.

I worked for several years as executive director of the Fellowship of Reconciliation, which I think through John Heidbrink, helped to bring Merton and the Berrigans into the work for peace in 1960 and 1961. I learned like Merton through FOR [Fellowship of Reconciliation] that all the major religions are rooted in nonviolence. Islam means peace. Judaism upholds the magnificent vision of shalom, where people beat swords into plow shares and study war no more. Gandhi exemplified Hinduism as active nonviolence. Buddhism is all about compassion toward all living beings. Brace yourselves, Merton teaches, even Christianity is rooted in nonviolence.

The one thing we can say for sure about Jesus is that he practiced active, public, creative nonviolence. He called us to love our neighbors; to show compassion toward everyone; to seek justice for the poor; to forgive everyone; to put down the sword; to take up the cross in the struggle for justice and peace; to lay down our lives, to risk our lives if necessary, in love for all humanity, and most of all, to love our enemies. His last words to the community, to the church, to us, as the soldiers dragged him away, could not be clearer or more to the point: "Put down the sword."

Now you might say this is the one moment where violence is justified. Peter was right to take up a sword, to kill to protect our guy, the Holy One. But Jesus issues a new commandment: "Put down the sword." That's it. We are not allowed to kill. That's why they run away; they realize he is serious about nonviolence, that we follow a martyr.

Jesus dies on the cross saying, "The violence stops here in my body, which is given for you. You are forgiven, but from now on, you are not allowed to kill." And God raises him from the dead, and he says, "Peace be with you." Then he sends us forth into the culture of violence on the mission of creative nonviolence.

I like how in one of his journals, in the early 1960s, Merton calls himself "a professor of nonviolence," determined to teach the church, even the world, the wisdom of nonviolence. We too need to teach nonviolence, and to call the church to practice the nonviolence of Jesus, and to help it reject the just war theory and accept the risen Christ's gift of peace.

Third, Merton invites us to become apostles of nonviolence.

We remember Merton's famous article for Dorothy Day and The Catholic Worker, where he wrote: "The duty of the Christian in this time of crisis is to strive with all our power and intelligence, with our faith and hope in Christ, and love for God and humanity, to do the one task which God has imposed upon us in the world today. That task is to work for the total abolition of war. There can be no question that unless war is abolished the world will remain constantly in a state of madness and desperation in which, because of the immense destructive power of modern weapons, the danger of catastrophe will be imminent and probable at every moment everywhere. The church must lead the way on the road to the nonviolent settlement of difficulties and toward the gradual abolition of war as the way of settling international or civil disputes. Christians must become active in every possible way, mobilizing all their resources for the fight against war. Peace is to be preached and nonviolence is to be explained and practiced. We may never succeed in this campaign but whether we succeed or not, the duty is evident."

Today [in 2005] there are 35 wars currently being fought with our country involved in every one of them. According to the United Nations, some 50,000 people die every day of starvation. Nearly two billion people suffer in poverty and misery. We live in the midst of structured, systemic, institutionalization of violence which kills people through war and poverty.

From this global system comes a litany of violence--from executions, sexism, racism, violence against children, violence against women, guns, abortion, and the destruction of environment, including the ozone layer, the rain forests, and our oceans. Since 2003, we have killed over 135,000 Iraqis. But on August 6, 1945, we crossed the line in this addiction to violence and vaporized 130,000 people in Hiroshima and another 70,000 people, three days later in Nagasaki.

Today, we have some 25,000 nuclear weapons with no movement toward dismantling them; instead, we increase our budget for killing and send nuclear weapons and radioactive materials into outer space. We put missile shields around the planet, and plan even greater nukes.

I think we are called to be activists for peace like Thomas Merton. Jim Douglass told me that Merton, alone in his hermitage in the woods, did more for peace than most peace activists. I think that whatever we do, wherever we are, we have to be involved in the movements for peace and justice. None of us can do everything, but all of us can do something, like Merton, whether through our prayer vigils, marching, leafleting, protests or civil disobedience.

So I urge you to join Pax Christi, the international Catholic peace movement, or the Fellowship of Reconciliation; to be part of the ONE campaign working to lift the third world debt; and the ongoing campaign to close the School of the Americas.On August 6th, the 60th anniversary of the U.S. atomic bombing of Hiroshima, hundreds of us from Pax Christi will go to Los Alamos, New Mexico, the birthplace of the bomb, and in a spirit of prayerful, active nonviolence, we will put on sackcloth and ashes to repent of the sin of war and nuclear weapons and pray for the gift of nuclear disarmament. I hope you will join us, or you own local peace vigil.

On the first page of his book, Peace in the Post Christian Era - which was suppressed until its publication by Orbis Books - Merton writes: "Never was opposition to war more urgent and more necessary than now. Never was religious protest so badly needed." (Peace in the Post Christian Era, Orbis Books, 2005.)

Fourth, Merton invites us to become visionaries of nonviolence.

One of the many casualties of the culture of war is the imagination. People can no longer imagine a world without war or nuclear weapons or violence or poverty. They can't even imagine it, because the culture has robbed us of our imaginations.

We live in a time of terrible blindness, moral blindness, spiritual blindness, the blindness that will lead us over the brink of global destruction.

Our mission is to uphold the vision of nonviolence, like Merton, to point the way forward, the way out of our madness, to lift up the light, to lead us away from the brink.

We need to be the community of faith and conscience and nonviolence that lifts up the vision of peace, to help others imagine a world without war or nuclear weapons, the vision that teaches us to resist our country's wars and nuclear arsenal.

All my life, I've been trying to uphold a vision of a world without war, by serving the poor and homeless, visiting the war zones of the world, organizing protests and getting arrested 75 times, engaging in a Plowshares action, and working at the Fellowship of Reconciliation. Now I live way out in the desert of New Mexico where until recently I've been serving as the pastor of several churches among the very poor. It's like being a desert father on the margins. New Mexico is a land of great spirituality, but it's also the poorest state in the US, the birthplace of the bomb, and number one in nuclear weapons spending, and these days I'm in a lot of hot water for calling for the closing of Los Alamos. But I remember that Merton visited New Mexico twice before leaving for Asia and was impressed by its land and people and life on the margins. He knew that this was a special place with the potential of becoming a land of nonviolence.

You may have heard what happened to me recently. I had been living in a small desert town in northeaster New Mexico, serving five parishes, and speaking out against the war, when one morning, on November 20, 2003, the day after it was announced that the local unit of the National Guard was going to Iraq, at 6 a.m., 75 soldiers came marching down the street in front of my rectory and church, shouting battle slogans. They marched passed the church for an hour, then the shouting got real loud and I looked out the window and discovered that they were standing right in front of my house, filling up the street, shouting out, "Kill, kill, kill!" So I went out and gave them a speech, saying, "In the name of God, I order you to quit the military, not to go to Iraq, not to kill anyone or be killed, and to follow the nonviolence of Jesus because God does not support war, God does not bless war, God does not want you to wage war." They looked at me with their mouths hanging open, and then broke up laughing. So now, I'm totally notorious.

But I've been telling my peace movement friends that after you become completely notorious, I no longer have to go to demonstrations. From now on, the soldiers come to me!

Like Merton, we all need to become new abolitionists who imagine a world without war, poverty or nuclear weapons.

Fifth, Merton invites us to become prophets of nonviolence.

Here is one of my favorite Merton quotes: "It is my intention to make my entire life a rejection of, a protest against the crimes and injustices of war and political tyranny which threaten to destroy the whole human race and the whole world. By my monastic life and vows I am saying NO to all the concentration camps, the bombardments, the staged political trials, the murders, the racial injustices, the violence and nuclear weapons. If I say NO to all these forces, I also say YES to all that is good in the world and in humanity."

I think that just as Merton learned to make his life a rejection of war by speaking out for peace, we must do the same thing and make our entire lives a rejection, a protest against the crimes and injustices and wars and nuclear weapons of our country and so become prophets of nonviolence to the culture of violence.Merton teaches us to break through the culture of war and denounce the false spirituality of violence and speak the truth of peace and nonviolence. Remember how he wrote to Jean LeClerc, that the work of the monastery is "not survival but prophecy," in the biblical sense, to speak truth to power, to speak God's word of peace to the world of war, to speak of God's reign of nonviolence, to the anti-reign of violence. I think that's our task too--not survival, but prophecy.

Merton wrote to Daniel Berrigan in 1962, "If one reads the prophets with ears and eyes open then you cannot help recognizing our obligation to shout very loud about God's will, God's truth, and God's justice."

I'm sure Merton would have something to say about everything that is happening the world today, in this whole culture of war. So like Merton the prophet, our job is to call for an end to war, starvation, violence and nuclear weapons, to say, bring the troops home, end the U.S. occupation of Iraq, cut off all military aid to the Middle East and help the U.N. pursue nonviolent alternatives to this crisis.

In March 1999, I led an FOR delegation of Nobel peace prize winners to Baghdad. We met with religious leaders, like the Papal nuncio and Imans, United Nations' officials, non-governmental organizations, and even government representatives. But, most importantly, we met with hundreds of dying children and saw with our own eyes the reality of suffering inflicted by the sanctions, because we have systematically destroyed Iraq's infrastructure by our bombs. Everywhere we went, the suffering people asked us right up front: Why are you trying to kill us?

Just as Merton condemned the Vietnam war and nuclear weapons and racism, I believe he would condemn the U.S. bombings, sanctions, and occupation of Iraq as a total disaster, a spiritual defeat. Iraq is not a liberated country. It is an occupied country, and we are the imperial, military occupiers. There is no representative democracy in Iraq, nor do we intend to create one, and if we are going to take the example and teachings of Merton seriously, then we have to do what he did and speak out against this horrific war. We're not cloistered monks or hermits, so we don't have any excuse.

The occupation of Iraq is not about September 11 or stopping their weapons of mass destruction, since they were destroyed. It's not about concern for democracy or disarmament or the Kurds or the Iraqi people.

If we cared about democracy, we would have asked them how to bring democracy, as we did on our delegation. To a person, they said, "Don't bomb us. Give us food and medicine and fund nonviolent democratic movements." Instead, we responded militarily with sanctions and bombs.

If we cared about the possibility of Iraq having one part of a weapon of mass destruction, we would dismantle our 20,000 weapons of mass destruction. As I said in a recent protest in Santa Fe, if President Bush was looking for weapons of mass destruction, we found them: they're right here in our backyard. He does not need to bomb New Mexico; just dismantle our entire nuclear arsenal!

This war is all about Bush and Cheney's goal to control Iraq's oil fields, at any price, to gain financial control of the world economy. We bombed every single major building in Baghdad except for the Ministry of Oil. We have an imperial economy based entirely on oil and weapons, and to maintain this empire, we have to wage war and wars require the blood of children, the blood of Christ. You and I have to become, like Merton, the voice of the voiceless, the voice of sanity and peace.

"I am on the side of the people who are being burned, bombed, cut to pieces, tortured, held as hostages, gassed, ruined and destroyed," Merton wrote in the 1960s. "They are the victims of both sides. To take sides with massive power is to take sides against the innocent. The side I take is the side of the people who are sick of war and who want peace, who want to rebuild their lives and their countries and the world."

|

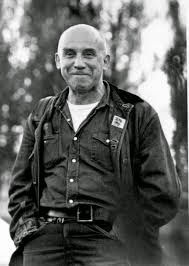

| Father John Dear. Peace activist. |

"It is absolutely necessary to take a serious and articulate stand on the question of nuclear war, and I mean against nuclear war," Merton wrote in the 1960s to his friend Etta Gullick. "The passivity, the apparent indifference, the incoherence of so many Christians on this issue, and worse still the active belligerency of some religious spokesmen is rapidly becoming one of the most frightful scandals in the history of Christendom."

If we are to be prophets of nonviolence like Merton, we have to speak out for an end to the occupation; call for the immediate return of our own troops; and call for the U.N. to resolve the crisis nonviolently and heal our Iraqi brothers and sisters.

We also need to call for an immediate end to all U.S. military aid to Israel and the occupation of the Palestinians, and instead fund nonviolent Israeli and Palestinian peacemakers, and say we're not anti-Semitic nor do we support suicide bombers, but that we want the Jewish vision of shalom. We support human rights for Palestinian children.

We must also demand that our country stop bombing and sending military aid to Colombia and the Philippines; close our own terrorist training camps, like the School of the Americas at Fort Benning, Georgia, as well as the CIA, NSA, and the Pentagon; and lift the entire third world debt.

We must demand that we cut our military budget; end the Star Wars missile shield program; dismantle every nuclear weapon and weapon of mass destruction, and undertake international treaties for nuclear disarmament; join the World Court and uphold international law; and then, redirect those billions of dollars toward the hard work for a lasting peace through international cooperation for nonviolent alternatives; to feed every starving child and refugee on the planet, end poverty, show compassion to everyone and protect the earth itself.

Merton teaches us, like Ezekiel and all the prophets, that whether we are heard or not, whether our message is accepted or not, our vocation is to speak the truth of peace, to become prophets of nonviolence, a prophetic people who speak for the God of peace.

Merton concludes his great essay, "Blessed are the Meek", on the roots of Christian nonviolence, by talking about hope, saying our work for peace and justice is not based on the hope for results or the delusions of violence or the false security of this world, but in Christ. Our hope is in the God of peace, in the resurrection.

Merton gives me hope: hope to become a contemplative and mystic of nonviolence and commune with the God of peace; hope to teach the wisdom of nonviolence to a culture of violence; hope to practice active nonviolence in a world of indifference; hope to speak out prophetically for peace in a world of war and nuclear weapons; hope to uphold the vision of peace, a world without war in a land of blindness and despair.

I looked up Merton's concluding advice to Daniel Berrigan in one of Merton's letters, and thought we could all take heart from Merton's encouragement: "You are going to do a great deal of good simply stating facts quietly and telling the truth," Merton wrote to Dan. "The real job is to lay the groundwork for a deep change of heart on the part of the whole nation so that one day it can really go through the metanoia we need for a peaceful world. So do not be discouraged. Do not let yourself get frustrated. The Holy Spirit is not asleep. Keep your chin up."

So I urge you not to be discouraged, not to despair, not to be afraid, not to give in to apathy, not to give up, but instead, to become contemplatives, teachers, apostles, prophets, and visionaries of Gospel nonviolence: to take up where Merton left off, to go as deep as Merton did, to stand on Merton's shoulders, to transform the church and the world into the community of Gospel nonviolence, so that we might do God's will, and announce like Merton, with Merton, the revelation of justice, the good news of the revolution of love.

So let us pray:

God of peace, make us contemplatives of nonviolence, prophets of nonviolence, teachers of nonviolence, apostles of nonviolence, and visionaries of peace like Thomas Merton. Help us to announce the Revelation of Justice and the Revolution of Love, that we may all welcome your reign of peace. Amen.

God of peace, give us courage and strength and faith to say NO, like Merton, to the evils of violence, war, greed, poverty, and nuclear weapons, and to say YES, like Merton, to Jesus' reign of nonviolence, love, justice and peace. Amen.

God of peace, we are blind. Give us the vision of peace to see every human being on the planet as our sister and brother, to love our neighbors and our enemies, to learn like Merton, that in the end, we are all one in you. Disarm our hearts and send us forth into a world of war and nuclear weapons, like Merton, like Dorothy Day, Martin Luther King Jr, and Mahatma Gandhi, that we too may be instruments of your peace. Amen.

| |||

| His Holiness the Dalai Lama visits the grave of Thomas Merton. |

We welcome your views. You are hugely welcome to leave comments on this page (below) or on Stephanie Dowrick's public Facebook page. You will support this entirely voluntary Book Club by using the bookstore links above right - and by sharing the link to this or any other article which contributes to a more peaceful world.

We would particularly recommend that you explore further writings from Thomas Merton. We would suggest A Thomas Merton Reader, available postage free in Australia from this LINK. (Postage free from the Book Depository link above right for those outside Australia.)

You may also appreciate Stephanie Dowrick's book, Seeking the Sacred (separately published in the US by Tarcher/Penguin), and - here at the Book Club - her recent assessment of James Hillman's A Terrible Love of War . You can visit InterfaithinSydney's YouTube channel to hear Stephanie Dowrick speak on peace, as well as other topics. Not least, those of you in or visiting Sydney are invited to join us for unifying sacred services each 3rd Sunday of the month, 3pm, at Pitt Street Uniting Church, Sydney, led by Reverend Dr Stephanie Dowrick.